This blog will contain the articles related to Entrepreneurship and human resources.

Thursday, May 19, 2016

Are you a Likely CEO?

Most of the people today are having the dreams of becoming entrepreneurs and CEO. Take this small quiz to know whether you are a likely CEO?

http://www.strategy-business.com/feature/Are-You-a-Likely-CEO

Wednesday, May 11, 2016

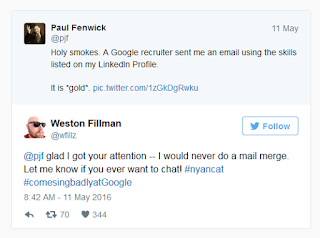

A Google recruiter sent this hilarious email using the exact skills listed on someone’s LinkedIn profile

Recruitment emails from big companies are notoriously

impersonal and packed to the gills with corporate marketing-speak.

So Paul Fenwick, a programmer in Melbourne, Australia, was

surprised to receive a message last summer from “People Operations” at Google

that sounded remarkably human, even funny.

According to tweets from Fenwick, the recruiter appealed

to his listed interests on LinkedIn, including his love of Nyan Cat costumes

and telling people they’re wrong. (It appears he has since updated his

interests on his profile.)

Fenwick tweeted that, since recruiters on LinkedIn are

often so lame, he had ignored the message until recently.

It seems Weston Fillman, the Google recruiter, has

thoroughly read the rules and still won’t give up:

He writes to Quartz: “I sent [the email] to Paul in a

creative effort to get in touch and play off his apparent sense of humor which

was found on his LinkedIn profile. It took him almost a year to respond, but

I’m glad he did.”

Source:

How to know the percentage of Highly Engaged and Highly Disengaged employees in your country

Many of us would like to know the people around us. We want to know how many of working professional are satisfied and how many are dissatisfied with their jobs. Also, we want to know the reason behind it. So here is the report which tells us all in the detail.

The Steelcase Global Report suggests that

28% of Indian Employees are Highly Engaged and Highly Satisfied while

4% of Indian Employees are Highly Disengaged and Highly Dissatisfied.

To get the detail report about your country, please visit below link:

http://info.steelcase.com/global-employee-engagement-workplace-report#engagement

Sunday, May 8, 2016

Winning hearts and minds in the 21st century

Leaders must consider new ways to change the attitudes and behavior of employees.

The psychological contract that traditionally bound employees to their employers has been fraying. Many of today’s workers, having experienced the pain of the economic downturn and large-scale layoffs, no longer feel as much loyalty and commitment to their organizations as they did even a decade ago. Job hopping has been described as the “new normal,” and millennials are expected to hold 15 to 20 positions over the course of their working lives.

To counter these problems, it’s more important than ever for companies in transition to invest time and effort in changing the mind-sets and behavior of the workforce. Almost 15 years ago, we introduced the idea that four key actions could work together to support such initiatives: fostering understanding and conviction, reinforcing change through formal mechanisms, developing talent and skills, and modeling the new roles. New research has since reinforced the significance of these four priorities.

The challenge for executives now is that they must learn to apply the model in new and imaginative ways that would not have been possible when we first published our research, at a time when the world was a very different place (exhibit). Back in 2003, the iPhone had yet to be released. There was no such thing as Facebook, much less Chatter, Twitter, or Yammer. The more fortunate millennials were off at college and still dreaming of the success they would eventually have from launching start-ups like Box or Instagram. Uber was just a German word. We rented movies at Blockbuster, drove around in Hummers, and read Newsweek—all of which have since folded.

Two key features of the modern workplace are particularly important in the context of change. One is the increasingly advanced technological and digital landscape, including mobile connectivity and social media, that has opened up exciting new possibilities for influence. The second is the new generation of millennial employees. On the surface, at least, they seem to have different needs and respond to change in ways that set them apart from their more tenured coworkers—though we’d echo our colleagues’ view (see “Millennials: Burden, blessing, or both?”) that their attitudes, in some ways, reflect those of the workforce as a whole. In the face of these interrelated opportunities and challenges, here are some ideas on how to win hearts and minds in the modern era.

New tools for influence

Digital advances can turbocharge efforts to foster understanding and conviction, thereby helping employees to feel more involved in change efforts and better able to play a role in shaping them. Consider, for example, how modern digital communications make it easy to personalize messages, tailoring them to the needs of individuals and delivering them directly to frontline employees. We take such personalized communications for granted, but they are significant in the context of major change efforts: they help to prevent a break in the cascade when a message trickles down from the CEO through middle management. For example, a global pharmaceutical company engaged in a major change program used its internal social-media platform in exactly this way, sharing different messages with different groups of users and ensuring that communications stayed relevant.

Technology also can help identify obstacles to change, such as overconfidence in your abilities or knowledge. Consider the popular FitBit and other activity trackers: these small devices provide an accurate (and sometimes surprising) picture of individual activity, expose the truth, and hold users accountable for their performance. Rapid-fire online-polling tools make it relatively straightforward to take an organization’s pulse, identifying differences in outlook and understanding between top management and the rank and file. Research based on McKinsey’s Organizational Health Index suggests that management frequently overestimates the impact of its messages on employees (for more, see “Why frontline workers are disengaged”).

Social platforms are more than just tools for communication and for building skills and a sense of community. They provide a sophisticated analysis that reinforces role modeling and builds up a momentum of influence. Over the past couple of years, we’ve seen a growing number of companies use social-networking analyses and similar techniques to help identify hidden influencers: people whose attitudes may command respect among their colleagues and whose role might be critical for the success of a change program. Having identified a few dozen influencers across regions, functions, and roles in this way, a large manufacturer we know enlisted the support of these employees to help communicate the changes it wanted to make, role-model the desired mind-sets and behavior, and fight skepticism.

New employees, new challenges

Indeed, the power of the group may be the most potent influence of all. Today’s increasingly connected digital world provides more opportunities than ever to share information about how others think and behave. Millennials typically take their cue from positive reviews on Instagram, SnapChat, or Yelp or from “Twitterati” with many followers. It’s no surprise that users of social media can “buy followers,” thereby boosting the popularity of a person or brand when it starts trending. Millennial workers, sometimes described as “hyperconnected globally,” may be especially open to persuasion through the collective voice and expect real-time communication from everyone, not just top management.The potential of technology to inspire action is good for would-be change agents, because today’s employees are increasingly skeptical. A generic change story won’t cut it now, if it ever did. To change hearts and minds, a story must be personally meaningful to the listener or reader. That’s particularly true for today’s younger employees. Recent interviews with hundreds of high-potential millennials, for example, revealed how, in many cases, their decisions to stay with or leave a company depended upon their ability to find meaning and purpose within it.

Technology’s new transparency, though, can be a double-edged sword. In today’s world, sites like Glassdoor take the mystery out of salaries and increased job mobility. That makes it easier than ever for employees to judge when they are unhappy with the direction of a company or decide that they are not getting an equitable deal. Remember, some twentysomethings recall how their own parents were mistreated in previous bouts of cost cutting, and many jaded older employees remain in the workforce. Organizations hoping to win over such employees need to do what’s necessary to neutralize compensation as a source of anxiety and focus instead on what really matters. For some workers, extra flexibility and telework may be more alluring than a bigger paycheck. Leaders directing significant change efforts should look at all the formal reinforcing mechanisms at their disposal.

Finally, don’t overlook skill building as a means of fostering commitment in the younger generation; millennials, after all, appear to be particularly hungry for opportunities to develop. The previously mentioned McKinsey research on this generation found many who were eager for advancement opportunities and receptive to various learning programs—from entrepreneurial challenges to more traditional rotational programs. In the past few years, organizations have started to tap into this mind-set, and some are exploring discounted education as an employee benefit. Starbucks’s college achievement plan, for example, now pays tuition fees for part- and full-time workers taking Arizona State University’s courses. Other organizations, such as Anthem and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, have since launched similar programs.

Millennials may seem challenging. Yet their search—for diverse role models, meaning beyond a paycheck, equitable treatment in an increasingly transparent and transient world, and leading-edge skill building—is one that many employees, regardless of age, industry, or nationality, are undertaking today. Leaders who understand both the changing workforce and leading-edge digital tools and have a well-tuned grasp of the building blocks of organizational change should be well positioned to break through the noise and inspire these employees.

Source:

Friday, May 6, 2016

Is it Worth a Pay Cut to Work for a Great Manager (Like Bill Belichick)?

Bill Belichick of the New England Patriots is one of the highest-paid coaches in the National Football League; Forbes in 2013 estimated his salary as $7.5 million. His track record helps explain the high compensation: Belichick is the first head coach to enjoy double-digit victories in 13 consecutive seasons, and is the second, after Chuck Noll, to win four Super Bowls. He has coached the Patriots to 13 division titles in 16 years.

Arguably, Belichick and the Patriots have dominated the NFL longer than any other team since the NFC-AFC merger in 1970. But is his ability to extract world-beating performances out of some good-but-not-great players and even to motivate others to take pay cuts in order to play for him, an anomaly? Can unusually gifted managers improve employees’ performance to such an extent that it is a rational decision to take less to work for them?

Some academic research indicates the answer is yes. That is, by enhancing employee value managers can potentially add significant value to an organization.

This research is particularly important to recall this week, when, with the close of the NFL’s regular season, teams fire underperforming coaches and hire new ones. Are coaches worth the multimillion-dollar salaries they are offered? Is the same true of managers in the business world? Just what is the value of a top manager to the organization and employees?

Do baseball managers improve performance?

In 1993, Lawrence Kahn analyzed data from Major League Baseball, drawn from the 1969–1987 period, to estimate the impact of managerial quality on team and on individual players’ performance. Using a team’s winning percentage in a given year as the dependent variable, managerial quality, winning percentage in the previous year, and additional controls, he empirically demonstrated that a manager’s ability was a very important factor in converting player performance into team victories in baseball.

But it wasn’t just team performance that was enhanced by managerial quality.

“Kahn’s additional analysis showed that great coaches help players achieve better individual performance”

Kahn’s additional analysis showed that great coaches help players achieve better individual performance. Furthermore, he empirically documented the impact of newly hired great coaches, showing that “when a high-quality new manager takes over a team, the average starting player's performance relative to his lifetime statistics (accumulated under other managers) is greater than when a low-quality manager takes over the team,” he wrote in his paper, Managerial Quality, Team Success, and Individual Player Performance in Major League Baseball.

Subsequently, these players might be able to monetize their newly acquired levels of performance, either with their team or elsewhere.

On the football field

In the football world, Coach Belichick is known for meticulous attention to detail and for his defensive strategy. His eye for talent and his ability to elicit the most from his players—whom he uses in unusual positions and unconventional formations—have helped the Patriots maintain a high level of play year after year, despite their typically low draft position.

At the same time, Belichick has helped individual players magnify their abilities and excel. As Kahn demonstrated, great coaches do not just help teams win; they also help players achieve their fullest potential. That’s why some players are willing to work for less for great coaches creating a competitive advantage for their teams.

Several players have benefited handsomely from playing under Belichick. Consider Deion Branch. When the Patriots drafted the wide receiver in 2002, he signed a five-year $2.93 million contract. Though initially listed third on the depth chart, Branch started 11 of 15 games in 2003, leading the team with 57 catches for 803 yards; in Super Bowl XXXVIII, Branch caught 10 passes for 143 yards and a touchdown.

The following season, after suffering an injury, Branch finished the regular season with 35 receptions for 454 yards and four touchdowns. In the AFC Championship, Branch scored the first and last touchdowns, the final one a 23-yard run on a reverse, which clinched the game after the Pittsburgh Steelers had clawed their way back to be down by just a touchdown. Two weeks later, Branch tied a Super Bowl record with 11 catches for 133 yards and became the first receiver to be named Super Bowl MVP since 1989.

Though Branch’s statistics did not match those of the top receivers in the game, he earned a reputation as a big-game performer. In 2006 the Patriots offered him a three-year $18.85 million contract with $4 million signing bonus but Branch held out for more, sitting out preseason games and the first game of the regular season; the Patriots fined him $600,000. Later that year the Patriots traded Branch to the Seattle Seahawks; he signed a six-year $39 million contract extension with a $13 million signing bonus with the Seahawks.

The rich deal monetized Branch’s performance with the Patriots, capitalizing on his reputation as a big-game competitor and paying him far more than his statistics justified. In five years with Seattle, Branch started only 40 games and failed to fulfill his promise as a top receiver.

A pay cut pays off

Next, consider Corey Dillon. When the Cincinnati Bengals’ all-time leading rusher was traded to the Patriots in 2003, he had been scheduled to earn $3.3 million in 2004 and $3.85 million in 2005. Dillon voluntarily restructured his contract—effectively taking a pay cut of over $3.6 million—to facilitate his trade to the Patriots and play for Belichick.

In 2004, playing for the Patriots, Dillon rushed for 1,635 rushing yards and 12 touchdowns, setting career highs and franchise records. Dillon played a major role in New England’s victory in the divisional playoffs. And New England won its third Super Bowl thanks to a running game built around Dillon. In recognition of his performance, the Patriots restructured Dillon’s contract and paid him a guaranteed $10 million over two years and $25 million over five years.

The examples of Branch and Dillon illustrate that playing for a great coach paid off for both players. Dillon took a pay cut for a chance to make the playoffs and win a Super Bowl, and Branch took advantage of his performance under Belichick and was paid handsomely elsewhere, though it turned out that his performance was not as portable as he believed it to be.

What managers can learn

Kahn’s study on the effect of managerial quality on baseball team performance and Belichick’s example in practice offer valuable lessons that support the hype generated when coaches are hired.

First, all other things being equal, managerial quality strongly influences a team’s performance in baseball as well as football. In fact, Kahn finds that changing managers may affect a team positively when a newcomer is superior to his predecessor. In addition to winning, great managers increase teams’ revenues over their compensation costs. From a corporate point of view, this implies hiring and succession planning processes are very important in leveraging great executives and managers. It pays for firms to invest in hiring and developing great managers.

Second, a given year’s winning percentage is not affected by the previous year’s winning percentage controlling for other important factors; only current performance, influenced by managerial quality, matters. This finding implies that a team that keeps on winning does so because the manager influences the team’s ability to keep winning. In short, a manager can teach a team to win; Kahn argues that the winning habit is learned top down in an organization.

Kahn’s study offers additional insights.

An average player’s performance in a given season relative to his lifetime average improves more for a higher-quality manager than for a lower-quality counterpart. Great managers deploy their players by putting them in situations where they have the highest chance of success. Through training as well as motivations, even average players might become rising superstars.

"It pays for firms to invest in hiring and developing great managers"

In the corporate world, this is analogous to team leaders utilizing skillsets of their team members in jobs and on projects that enable them to excel and to showcase their talents. If people have the expectation that they can monetize the value of their improved performance, they will be more willing to accept a lower starting salary to work for a better manager. Great corporate leaders thus provide another source of competitive advantage because they have the potential to attract, leverage, and retain talented employees at lower overall cost to the firm.

Overall, one can conclude that teams that hire great managers get increased team and individual performance. Giving these findings, Kahn argues that hiring great managers is truly a bargain, both for the organization and for individual players. And yes, it can be a smart move to take a pay cut to work under a great leader. The career of Bill Belichick represents a notable example.

Source:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)